John Welsford and his new design – Long Steps.

In a recent poll the members of the John Welsford designs Facebook group voted Long Steps as the boat they would like to own if they could only own one of his designs. Given that many of the members that voted already owned other of his designs – me for one, it was fascinating to see that particular design come out ahead of the pack. I for example am building a modified example of his Pathfinder design although I happen to think that Long Steps might be a better boat for my sail and oar project ; the main reason that I didn’t start on Long Steps instead of Pathfinder is that she is a longer boat by two feet and I suspect wouldn’t go in and out of our driveway…..my Pathfinder is about at the limit of a boat that I can keep at home and it’s also an excellent boat for most of my project.

Going back three years now I had to make the difficult final decision about which boat to commit to building and right up until the last moment I wasn’t sure about which boat I would build : in the end I my decision was based on building the largest, fastest and most powerful sea-boat at around 17-18 feet that I could that would also make a viable expedition boat. I happen to think that Pathfinder is still a great boat and right now I hope that my modified example will do the job – which is to sail and row around the UK in a mostly open boat and while doing so to put into as many of the small harbors, rivers, estuaries and creeks as I can. My Pathfinder should do a great job of the sailing as it’s a dedicated, powerful sailing boat design but I might struggle a bit with it when it comes to the rowing and sculling which is where Long Steps wins out…..as I understand it.

Long Steps in build. Photo courtesy of builder Audrey Laser.

Some why-not’s before the why’s.

After my enthusiastic post about John’s SCAMP design more than one person asked me why I hadn’t or didn’t build one myself, after all it was at the time a great new design and an easier one to accommodate at home . Also that several trips by various skippers demonstrated what a capable small cruising boat it was and in a way not ‘just’ a sailing dinghy. It wasn’t only just Howard Rice’s exploration of Tierra del Feugo and the Beagle channel under sail but events such as the Everglades challenge which now always seems to feature a SCAMP or two.

My simple answer is that I ‘ran the numbers’ on the various designs and one of the main ones I do is to approximately calculate a boat’s hull speed from it’s waterline length. I do also try to work out an approximate carry capacity because I am thinking of extended passages where I want to carry lots of water, food and stores. Now, don’t get me wrong – we know that SCAMP sails well, carry’s it’s load well and generally ‘punches above it’s weight’ but for the kind of sailing I do I figured that it might have a small boat speed problem and it might also not be a great rowing boat due to it’s length-beam ratio.

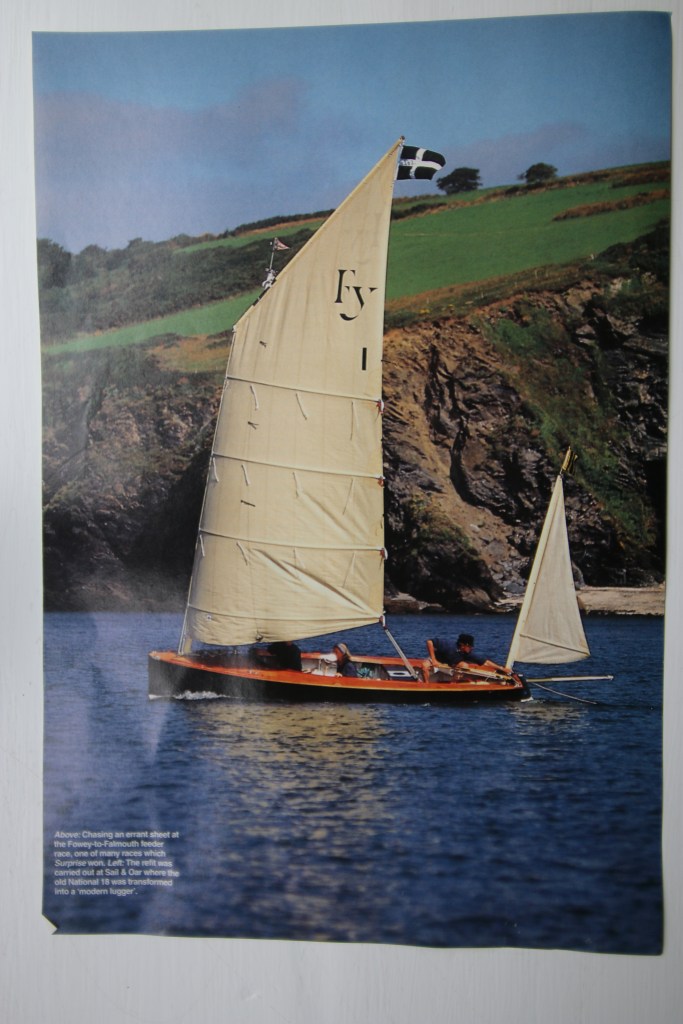

I suspect and have even calculated that in ideal ‘boatspeed’ conditions I could be and should be sailing at least a knot to knot and a half faster in Pathfinder when compared against SCAMP – the other side to that is that Pathfinder is designed to plane in ideal conditions where, once again, SCAMP is not. I don’t expect that it will happen very often but i’m sure i’ll have a lot of hooning around the place when it does. As a side note aside at this point I did keep in mind doing a conversion of a National 18 racing dinghy as a cruising boat ; there’s a Lug rig converted one on this coast that goes like that stuff off a shiny shovel but then it does help that it’s driver was once a National 18 champion !

One of the issues I had with that idea, and to some extent still have, is that while the National 18 would be a powerful and fast cruising boat it wouldn’t necessarily be a good expedition boat without a complete rebuild and re-work of the design. I might have this wrong but to make a good expedition boat needs more designed features than raw speed and power – as much fun as they would be. Now…..when I look at liitle SCAMP or larger Long steps I see two boats that instantly make a more expedition orientated boat in that both of them already have shelter built in, both of them have lots of reserve bouyancy and both of them seem to have sailing comfort and essentially what we might call ‘recoverability’.

Sail and oar, the problem.

I for one am fascinated by working boats that were intended for working under oars (or scull) and then scooting along under sail when conditions allowed ; the opposite is that of a more dedicated sailing boat that rows well. For anyone else as interested in the subject as I am there is an excellent reference work by John Leather called appropriately Sail and Oar. The problem comes when we expect a vessel to be good at two things which aren’t particularly compatible ; a rowing boat benefits from being ‘lean and mean’ to have less resistance in the water while a sailing boat benefits from form stability which mainly comes from beam (not always) and beamy boats can be a pain to row because they have a lot of surface area to create drag.

Right up until the moment that I bought the full plans to build Pathfinder I was still thinking about building one of John’s previous sail and oar designs called Walkabout, except that what I wanted to do was build one just like an extended Walkabout that had successfully sailed in an earlier Everglades Challenge. The original design is 16′ 2″ and the lengthened version about 17 feet which, once again, is just a tad under the maximum length of boat that I felt I could have at home. Building an extended version would have been a relatively easy conversion for an experienced builder (which I am not) in that it would have mainly been a matter of spacing out the building stations by a given amount and then drawing the bow section out by the same percentage – for some reason I was less than confident about doing that .

Walkabout – the extended version as sailed in the Everglades Challenge by ‘Chuck the Duck‘ and ‘Lugnut‘ (their Watertribe names)

Designing and building Long Steps.

If I have got this right then Long Steps is similar in concept to Walkabout, being designed to both sail and row, but is even more aimed towards the expedition mode of a sailing and rowing craft and has specific features built in for that role ; it’s also a longer boat by 3 feet. When I came to start work on my own build I knew from the outset that I was also trying to build what I thought an expedition should be and what I did was to take design features from both SCAMP and the new Long Steps design to incorporate into my own build. For anyone who followed my build this is where the off center ‘centerboard’ comes from, ditto the hard shelter/cuddy that both of those boats utilize but I didn’t go for water ballast as those two designs use because at an early stage I intended to carry dry ballast weight in the shape of a large fixed AGM battery.

One of the really nice things about being completely mentally engaged for 2 years in the building and now fitting out of my own boat has been watching the progress of two Long Steps in build ; John is building one for himself, which I feel says a lot about his confidence in the design while the other one is being built over the water at the Tasmania wooden boat center – that’s the actual build that I have mostly featured here courtesy of her builder Audrey Laser.

Long Steps….what the designer says.

Firstly – on the subject of expedition boats vs ‘harbor’ dinghies. For those readers as engaged as I am by the subject of small expedition craft then a very good place to start is the onlne discussion/interview between John Welsford and DCA (Dinghy cruising association) president Roger Barnes. In that session John lays out what he feels the differences are between a boat that you might sail around the harbor in for a few hours, on a nice day, and the kind of boat that you would choose if say you wanted to sail in exposed conditions over greater distance and have a boat that looked after you rather than one which tired you out after a few hours.

Very briefly and crudely put, the main differences between a general purpose dinghy, like the English Wayfarer for example, and something like a Pathfinder…..is that the expedition boat first needs to sail well but then it also needs to carry weight, needs enough reserve bouyancy to be easily recoverable in a capsize, needs to be rugged enough to cope with difficult groundings and importantly to be comfortable at sea and look after it’s crew. I would suggest that those are either designed features that make for an expedition boat or ones that have to be added in.

One quick way of understanding that difference, in my own take on the subject, is by looking back in the canon of sailing literature to the offshore voyages of Frank and Margaret Dye in their Wayfarer design (later on Frank and his later crew members). The Wayfarer is a great general purpose dinghy design but just one comment from Margaret Dye about one of their first major voyages is that she became quickly exhausted by the voyage and the boat. I got the sense that with careful sailing the boat would do the job but didn’t look after it’s crew well as they were constantly exposed to waves and spray.

My own version of that relates to a passage I did in 2019 in my lightweight centerboard cat-ketch, from the south west of England to the north western Brittany coast, thus across the wide end of the English channel. That passage is one that I intend to repeat in the Pathfinder and in a way is the test piece for the boat and which informs all of my choices about it’s set up. For those less familiar with English channel geography and conditions the passage from Fowey or Falmouth say to Roscoff is around a hundred sea miles and the same passage but to the north western ‘corner’ of Brittany at L Aber- Wrach is 110 miles. Both passages are similar in that of being across the wide end of the channel and it’s normal to experience a westerly swell coming up the channel from the Atlantic – during a spring ebb tide what then results is a horrible wind against tide situation which is exactly what I had when I made the crossing with the little Liberty in 2019.

Another feature of that end of the English channel is that it is crossed, east to west, by a pair of traffic separation zones which have to crossed at right angles and really need excellent watch keeping because of the density and speed of shipping traffic : at one point during my return crossing I could see the lights of some 14 ships.

On the outward journey that brisk wind against tide situation made me both incredibly cold (it was early in the season) and violently sick, my only protected watch position was to stand in the companionway being bounced off each side of the weather board slides and even with my foulies hood up my head still felt horribly cold in the biting easterly wind. Standing like that for hours on end was anything but restful and I determined that my next boat would have a sheltered and comfortable watch keeping position. I was inspired at that time by a photograph of one of the Walkabout crew in the Everglades challenge reclined and apparently asleep under the boat’s soft-top cuddy cover – that reclined position being made possible by Walkabout’s off-center board .

I can well imagine being sat reclined against one side or other of WABI IV’s hull, under her hard cuddy and only having to move aft a couple of feet to have a good look around the horizon on a long passage. In easier conditions I fully expect to be able to make a hot drink under the cuddy and do my navigation and log-keeping tasks there too. In most conditions it should be possible for one or the other of us to sleep under the cuddy too….especially if I go ahead with my plans for an extended tent cum sprayhood. I can’t say that I would be any less sick but I would be far more comfortable with my back supported against the cabin side (I have a plan for my soft stowage bags there which will form the backrets) and far warmer too.

In John’s own words shelter is one of the features that is essential in an expedition style boat and both of his recent designs, SCAMP and Long Steps both have off-center boards and hard shelter/cuddy’s.

But what about the rowing ?

Thus far iv’e said a lot about sailing because I am principally a sailor and for me the oars on my Pathfinder aren’t there to make distance with but mainly to help me pull up a short section of river to a quay perhaps or wherever I choose to anchor. My usual cruising situation isn’t getting my butt kicked in a nasty wind against tide in the English channel, rather it’s more about sailing coast-wise around the west country and then making my way up one of the ten rivers that form the interest of my home cruising ground. Nearly all of those rivers are formed by steep sided and wooded valleys, they really are lovely except for the fact that they give hard shelter from the wind – even when a bit of wind is just what I need, and of course they are strongly tidal.

One of my favorite things to do and best places to be is to be ghosting up the Fal/Truro rivers from Mylor just as the tide starts to make, to then sail as best I can with the gaining tide up past King Harry Ferry but then turn off the main river and anchor in the first bight of Ruan Creek (the actual river Fal) until there’s just enough water in the channel for me to make my way. In the past I often had to use the noisy outboard although my favoured thing to do was to deploy a canoe paddle either side of the boat and ‘power stroke’ my way up the channel until I could anchor in any one of my usual spots. I happen to think that that situation would be the perfect ‘problem’ for a set of oars, or even a single sweep oar.

It’s often been more the case that iv’e been at anchor far upstream in one of the main south western rivers and timed my passage such that I can ride the new ebb down to the river mouth without having to use the noisy outboard. On one occasion I just had to do that in hardly any wind when my outboard motor just wouldn’t even start and I had to get out of the Dart and around Berry head to meet up with my partner in Torbay. Once again that’s less about making distance because the ebb is doing most of the work, rather it’s about maintaining steerage way down through the moored yachts and getting past the cross-river ferries…..which don’t like giving way to small boats. In each of those situations a set of oars would have been ideal.

Those situations though are somewhat ‘passive’ when it comes to rowing and what is more difficult to achieve is a boat that can be pulled (rowed) over longer distance or say over a foul tide when there’s no wind or not enough – a foul tide and a light headwind is a difficult problem for the small craft sailor. In that situation it would help if the boat has much less resistance when it comes to rowing, essentially it needs to be a slimmer boat with finer lines and that seems to be what John has done with Long Steps.

Long Steps : long and lean and slippery.

Long Steps in other words.

In my previous post of this series, my post about John Welsford’s SCAMP design I was greatly aided by canoeist and sailor Howard Rice who pointed me in the right direction to find his magazine articles about his Beagle channel/Tierra del Feugo exploration with his modified SCAMP – Southern Cross. Thus far not much has been written about Long Steps but I owe a lot to the Tasmanian Long Steps builder – the artist formerly known as Audrey Laser ; who’s actual name is Mike and who is a retired surgeon who shares jokes about gynaecologists. That’s quite funny because right now I am often writing about Peter Gerard who’s real name was Dulcie Kennard and it’s also funny because I used to crew for a consultant gynaecologist name of JC who used to tell me bad jokes about anaesthetists and even worse jokes about his junior doctors……his regular joke was to tell his juniors to make sure they washed their hands after any procedure and his other routine was to subject me to vivas aboard the boat, during meal time, about anything to do with gynaecology.

Anyway, our man Mike, or Audrey is has been building a Long Steps design at the wooden boat center in far off Tasmania and was kind enough to share some of his experiences with the build thus far. Funnily enough I have been into Hobart (Tasmania) twice and the Beagle channel once and I would consider both to be extremely challenging places to sail in a small craft ; while I mainly referred to Howard Rice’s SCAMP voyage down in the Beagle channel I do know that he has also taken a sailing canoe down there. There’s a recent link with that for me because while we were creek exploring over in Norfolk I couldn’t help but think that what I really wanted there was a sailing canoe ; then, when we got home from that trip I noted that another regular contributor to the JW site (Lonnie Black) is building a sailing canoe to a design by Howard Rice and yes…..that gets me twitching a bit.

Of the three places in the world that I have sailed and consider to be actually very challenging one is the Beagle channel, another is South Africa for it’s strong winds and lack of shelter and the third is Tasmania. I’m glad that we had a generally benign trip across the bottom of Australia to reach Hobart but I guess that most readers here are familiar with what the Tasman and particularly the Bass strait can do during a rough Sydney-Hobart race. Given that it’s basically Southern Ocean conditions down there and has very little natural shelter it’s a very bold and unusual place to choose for small craft voyaging – anything I have to say about the problems of the English channel and the south west coast is amplified a good few times when thinking about the Tasman.

Those readers familiar with my blog will know that i’m fitting out my Pathfinder to do a circumnavigation of England (maybe even of the entire Island group) by sail and oar – my plan is a kind of Dylan-esque (Dylan Winter that is) voyage in that I intend to poke my nose into every river estuary and small creek that I can while filming it and blogging about it. Well, our man Audrey (mike then) is building and fitting out his Long Steps to do a solo circumnavigation of Tasmania and , like Howard Rice’s Beagle channel exploration I for one find that a very challenging concept when I compare it to my own plans.

Mike (our man Audrey) about the build.

At this stage very few examples of Long Steps have been finished and are on the water actually sailing. Designer John regularly posts updates about his own build which also seems to be both on a trailer now and at fitting out stage and as iv’e already mentioned I have been closely following the build of the Tasmanian boat. One annoying feature of this website is that I don’t seem to be able to post two photographs side by side as I once could ; if I could do that I would include a double picture of my Pathfinder and Mike’s Long Steps side by side at the same point in construction. The construction is remarkably similar because both boats are built with planks over stringers which go over bulkheads.

What Mike says about the build of his example of Long Steps is as follows and this is perhaps the result of it being an early example “Having built a few boats in the past helped particularly as the plans are young and only a few been built. The plans have a few quirks/inconsistencies that take some judgement to work out. JW always available to consult and very experienced friends advised……and……..Getting the lines/curves of the sheer and inwale looking good and in fair curves wasn’t easy. A few wibble/wobbles in curves and dimensions. Standing back and getting a fair,pleasing curve took a while and some help from the studio audience.“

While my experience of building Pathfinder was pretty straightforward except for some difficulty in reading off some numbers on the plans there was also a bit of the boatbuilders art involved because some stages do need to be done ‘by eye’ to get a fair curve. In my case the problems came more from the plans obviously having been printed many times with the result that some of the critical numbers were difficult to read plus the plans don’t quite read to scale as they once did. His experience was similar to mine own though because both John Welsford and other builders were very quick to offer solutions when problems came up – as mine did with exploding bilge chine stringers.

What John says about Pathfinder, and I assume is also true of Long Steps is that they are intermediate level boatbuilding rather than basic/starter level : there were a few times when I felt that I was being too ambitious in having chosen Pathfinder and to me Long Steps looks one stage more complex a build.

The ‘other’ aspects of expedition and ‘adventure’ sailing ; the adventure or expedition itself and the person who does it or has the dream of doing it.

One thing I took note of in Howard Rice’s stories about his SCAMP adventure is that he ‘had the dream’ for years and years before he was able to finally get to work on it. Then, when he did he seems to have thought about every detail of the boat and both built a modified version and one that had lots of additional detail over the standard boat : take a look at his rig, his shelter and his stowage for example.

Southern Cross – Howard Rice photo.

My version of that is features directly taken from both SCAMP and Long Steps – the hard cuddy shelter and off center ‘centerboard’ which gives firstly a sheltered watch space and secondly a larger working area on one side of the boat. I am also working on stowage, on the ergonomics of being able to handle and set sail as a singlehander and similarly working on the stowed position and handling of my multiple anchors. More features of an expedition boat are those that are built in by the boat’s skipper – for example how many and what type of anchors are carried – I happen to think that two is the minimum and wouldn’t object to a third.

The final, or primary element though, is perhaps the skipper or would-be skipper that does the dreaming, then the planning and the building in detail and only then gets to set out in a boat that he or she has taken time, years perhaps, to build.

Three years ago I could perhaps have found a viable replacement for my relatively small Hunter Liberty and at much less commitment of time and funds set off on my great adventure and by now be two years into it. It might be just me, although I know that Long Steps builder Mike in Tasmania is also thinking along similar lines, that there’s something special, unique even, about building the boat and going out on the great adventure in a craft that you have built yourself. My partner says that I must be clever to have built a boat although I think the ‘smarts’ is far more to do with the bloke that originally designed it and worked out a viable construction method that works for ham fisted dweebs like me.

It’s well past time I handed over to the actual designer who is also building a Long Steps for himself and has a voyage in mind.

Long Steps in the designer/builder’s own words.

Long Steps. What was I thinking? (John Welsford)

“My intention was to design a boat for my own use, I’ve had some interesting adventures during the years I’ve been around but it still feels as though the “life defining” adventure is still out there. I don’t really fancy Cape Horn, or the North West Passage, or even a circumnavigation, I enjoy my time in the workshop and although I live alone, the company of my friends. So I thought over the many coastal voyages I’ve done, quite a few in open sailing and rowing boats, and decided that a trip around New Zealands North Island might be a good goal. That’s quite a trip, the island is in the sub tropics in the north at 31 south and in the roaring forties in the gap between the north and south islands.

There are stretches of coastline where the only harbours are bar harbours with high risk entrances, the prevailing winds are strong, and there are no other land masses to shelter behind. So it’s a challenge. A boat to meet that challenge would need to be extremely seaworthy, essentially blue water capable, capable of self rescue in case of a full knockdown, capable of sailing on when fully swamped, capable of carrying her solo skipper in some degree of comfort when resting, or when hove to a sea anchor if need be, capable of keeping stores and clothing dry no matter what, and a whole lot of criteria along similar lines.

She was to be a “sail and oar” boat, now on the one hand my Walkabout design has proven to be a very capable rower, fast and comfortable for a single pair of oars, and also very good under sail but not quite tough enough for three or four days at sea. I’ve designed two ocean crossing rowing boats for clients, so have some experience in that area, a “solo” boat for a 2500 mile crossing would generally be around 7.2 metres or so long, and weigh in at around 2,200 kg and they row across oceans so a boat intended for a voyage where the prospect would be for a week or so maximum could be rather smaller, easier to row, and still, if I use the Walkabout hull type I know that sails well.

So, given all of those criteria I started drawing, there are a whole lot of hydrodynamic “numbers” that are predictors of performance, and I established those before a line was drawn , then came the sketch proposal, and the layout. In a boat that has to row well, the ergonomics for the rower have to work really well, 1300 strokes an hour on the oars is a lot of repetitions so the layout has to be such that there is no awkwardness or discomfort, so the boat is essentially designed around the rowing station.

John’s boat out in the winter sun for the first time and getting it’s masts in. John Welsford photo

As with Walkabout I’ve chosen the cat yawl, that’s a big main well forward and a mizzen down aft, that leaves the centre of the boat clear for the rower. The retractable centreboard is offset the rowing station is unobstructed by that, and the seat fronts being parallel rowing seat can be mounted between them and be able to move to the ideal position but still be shifted out of the way for sailing or to clear the cockpit trench to create a secure space for sleeping.

SCAMPs cuddy shelters a sleepers head and shoulders, plus provides a space out of the wind and rain for cooking, it is also just big enough for one to get in there, seated across the boat its not uncomfortable and is a great place to rest, as well, the forward part of the cuddy being divided off by a bulkhead with hatches for access gives air chamber buoyancy high up which helps the boats ability to resist a full roll over so that little dummy cabin is multi function.

The cockpit floor is raised with a big water ballast tank under, again a feature from my SCAMP design, and again as with SCAMP there is a huge amount of space in the air tank lockers under the seats, under the fore part of the cockpit floor and as with Walkabout there is a big airtight compartment under the stern deck. All this adds up to almost 2 tonnes of positive buoyancy, and the boat is so stable after righting that she can be sailed away from a capsize without having to be bailed out.

More on the rig, the mizzen is large enough to hold her close to head to wind, that means that the main boom is accessible without having to go up on deck to reef her, essential in a small boat at sea, the sail area being split between two sails well apart means that she will be able to maintain her course untended on quite a range of courses relative to the wind, which together with the ability to sit hove to bow on, makes her easy on her crew when on a long passage.

There are many other little touches, I’d planned on a plan of last resort being to run her up a beach if there was nowhere else to go, so she’s very shallow draft, and her rudder has an end plate on the rudder head, that being about 200mm below the waterline so she can still be steered with the rudder kicked up, it’s not as accurate but it does work enough to steer in very shallow water such as a river entrance.

Construction, I’m set up for plywood, have all the tools and machinery, am well practiced with that material, and for most of my customers it’s a material that’s accessible in terms of supply, skills needed, and tools, all of which makes it the easiest all round. So there are, as I write, about 40 sets of plans out there, four that I know of are complete and the reports on the boats performance and handling are very positive, and there are several, including my own, are very close to launching. “

Credit where credit is due….

I would like to offer my thanks to designer/builder John Welsford for taking time out of a busy schedule to write out his thoughts about Long Steps and allow me to use his work. Secondly I would like to thank Mike Vaughan for the same thing and I have included a lot of what he has said about the boat and the experience of the build.

Best wishes everyone.